Uber is trying out a new way of showing the cost of a ride, showing those seeking rides the maximum possible fare upfront – with a catch.

In Miami, Chicago and other cities where Uber’s carpooling service, UberPOOL, is available, Uber is experimenting with displaying the maximum uber fare estimate possible to customers, according to The Los Angeles Times.

Described by Uber as “upfront pricing,” this method will show the highest possible price of an UberPOOL, alongside the same for UberX. Uber will automatically calculate variables like the time of day, traffic conditions and estimated distance of travel, and customers will never pay more for a ride than the price that was displayed for their request.

“By ensuring that riders can easily see how much they can save by carpooling, we’re aiming to put more butts into fewer seats,” Uber spokesperson Tatiana Winograd told the Times.

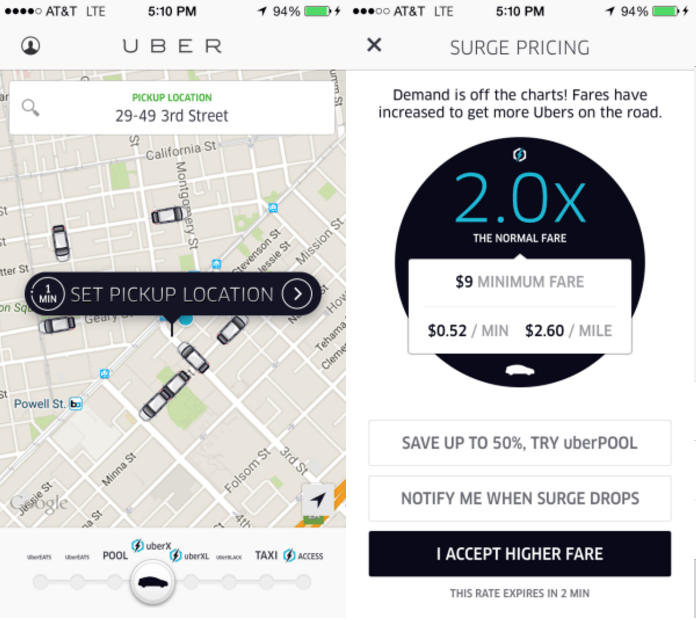

However, there appears to be another change: the “price surge” of an UberPOOL ride – that blue-number multiplier – is not being shown to customers in this display, Quartz reported.

UberPOOL is priced “dynamically,” but customers get a price quote instead of a “multiplier,” Uber New York general manager Josh Mohrer told Quartz in an email. “So is that ‘surge pricing?’ Yes and no.”

Uber has been quick as of late to quash rumors that it is ditching its “price surge” feature. When in April Jeff Schneider, lead engineer at Uber Advanced Technologies Center, suggested to NPR that price surging may go away, the ride-hailing outfit swiftly put out a statement denying this possibility outright.

“Uber is always looking for ways to better predict supply and demand in a city. But this story is not accurate: we have no plans to end dynamic pricing,” an Uber spokesperson told MarketWatch in a statement. “While we understand that no-one likes to pay more for the same trip, it’s the only way to ensure that passengers can always get a ride when they need one.”

The Case For Uber Removing Surge Pricing

From a behavioral economic standpoint, price surging is an incredibly complicated endeavor for ride-hailing services. Keith Chen, head economic analyst at Uber, spoke with NPR’s Shankar Vedantam earlier this month on the subject, highlighting that as traditional economics would predict, raising the price of a ride starts to lower demand.

“You know, when you go from kind of a surge of 1X, meaning no surge, to 1.2, you actually see a very, very large drop in demand – OK? And that initial drop in demand – actually early on when we first started surge-pricing at Uber, going from 1X to 1.2X, you would see a 27 percentage points drop in people who would request,” Chen said.

Recent research gives a similar narrative to the price surge. Christo Wilson, assistant professor at Northeastern University, worked with a team of researchers to do what they called “algorithmic auditing,” to try to crack open what they saw was a “black box” in how Uber calculated its surge pricing.

“They have this algorithm, and they say it changes prices based on supply and demand, but it’s a black box. You have to trust that it’s working correctly, because you can’t verify. You don’t know how many customers there are, you don’t know how many other drivers there are,” Wilson said.

Their research found that while surge prices do lower demand, they don’t always motivate drivers to go to busier areas. As well, demand can drop along with a surge, leaving some drivers who go toward it without passengers.

“What we see is that demand drops precipitously, cars stop getting booked and drivers are just sitting there. And actually there’s a lot of drivers who drive away from surges…If the incentive was working the way it should, you would expect there always to be an incentive for [drivers] to always move in. But in this case, the result is mixed,” Wilson said.

Uber Drivers Count on Surge Pricing

Despite how sick the surges may make its customers, Uber has a substantial incentive in keeping them around: their drivers really, really like them.

When NPR spoke with Uber drivers about the impact of surge pricing on their take-home pay, they found drivers said they really needed surge pricing to be able to afford being Uber drivers at all. One driver, Bloomington, IN-based Nathan Sapp provided three months of pay stubs, and NPR found that surge trips made up about a quarter of his earnings. Another driver, Atlanta-based David Thrasher, showed them stubs detailing a pay-scale increase of about 5$-6$, a substantial increase, during surge-priced rides.

In Chen’s conversation with NPR, he noted that what he sees in driver data is that some will double or even triple their shift lengths if there is a surge in the area they’re in.

“They’re just going to stay out because, well, they can make a lot of money right now. You know, they can take the whole weekend off if they put in another few hours today,” Chen told NPR.

It should be no surprise then that while Uber is experimenting with ditching showing customers when a surge is happening, they’re keeping that view around for their drivers, sticking with their app-based heat-map of potential customers and surges.

So while Uber is moving toward not showing the surges to their customers, they seem to be unable to eliminate the surge as it would hurt their ability to work with their supply-demand formula. This comes at a time when Uber’s main competitor, Lyft, appears to acting in a similar quiet fashion, removing their cap on price surging on rides without any public fanfare. In the end, as Schneider told NPR: “Nobody loves surge pricing.”